I recently interviewed Chuck Butler about winners and losers during inflationary times. I began with:

“Historically inflation hurt creditors and helped debtors as they are paying back their obligations in much-depreciated dollars. I’ve had readers ask about borrowing money to invest.

Chuck, that concerns me. Many of our readers are baby boomers or retired. …. Are you in the camp of believing that people should get out of debt and stay that way?”

Chuck responded, with my emphasis:

“Well, just because I say this, doesn’t mean it’s right for everyone, but for the most part, it should be right.

I have always been someone that doesn’t like to owe anyone anything… Therefore, I WOULD be in the camp of believing that people should get out of debt.”

What if we are wrong?

While I too believe getting out of debt is good, what if we are both wrong?

When my wife Jo and I paid off our home, we celebrated. While I have never regretted that decision, might emotions be clouding my judgment?

It’s time to take an in-depth look at our premise.

I Googled, “Does inflation favor lenders or borrowers?” Investopedia weighs in (emphasis mine):

“Inflation Can Help Borrowers

If wages increase with inflation, and if the borrower already owed money before the inflation occurred, the inflation benefits the borrower. This is because the borrower still owes the same amount of money, but now they have more money in their paycheck to pay off the debt.

…. In other words, cash now is worth more than cash in the future. Thus, inflation lets debtors pay lenders back with money that is worth less than it was when they originally borrowed it.”

Looking at the premise

Inflation helps the borrower – “because the borrower still owes the same amount of money, but now they have more money in their paycheck to pay off the debt.”

What if the borrower is retired, or close to doing so? Let’s take a hypothetical example.

Sam and Sally Smith live in Phoenix and are ready to retire from their high-stress jobs. They relied on stockbroker Joe for the last 25 years; their investments have done well. Joe now has a corner office and new title, “Senior Retirement Specialist”.

They asked Joe to “run the numbers” using his company’s retirement calculator, estimating their investment income, social security, projected expenses, inflation and projected longevity.

They used historic market and inflation data.

Joe showed them this Business Insider article:

“According to global investment bank Goldman Sachs, 10-year stock market returns have averaged 9.2% over the past 140 years. Between 2010 and 2020, however, the investing firm notes that the S&P 500 has done slightly better than the historic 10-year average, with an annual average return of 13.6% in the past 10 years.”

Joe was pleased to report they had done better than the 9.2% average, and suggested, “just to be safe” they should project an 8% return.

He presented this inflation data:

“The dollar had an average inflation rate of 2.36% per year between 1990 and 2018, producing a cumulative price increase of 92.22%.

This means that prices in 2018 are 1.92 times higher than average prices since 1990, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index.”

Joe said the Fed is currently targeting an “average” 2% inflation, and suggested, “just to be safe” they should use 3%.

They agreed and Joe hit ENTER. With the customary 4% annual withdrawal from their 401k, the calculator estimated they would have around $2,000/month after their estimated expenses of $75,000 annually; they could retire comfortably.

Sally then mentioned they want to buy a summer home in the cooler Arizona mountains.

Joe started probing. The home would cost $250,000 and they wanted to pay cash for it.

He punched some numbers in his computer and remarked, “If you put 20% down, our mortgage division will lend you $200,000 at approximately 4%, with payments around $1,000/month. Why would you take the money out of your investment account when you have been earning double-digit returns over the last decade?”

Joe showed them the retirement planner. Even with an additional $1,000 month mortgage, they still had plenty of money to pay their bills. If they kept the $200,000 in their account earning 10% it would total $20,000. Deduct $8,000 for interest, you still are $12,000 ahead. Your investment income pays for your mortgage. If times got tough, they could always pay it off later.

They followed his advice, bought the summer home of their dreams and now have a mortgage.

What could possibly go wrong?

I’ve been retired for 15 years and want to share some real-world experience.

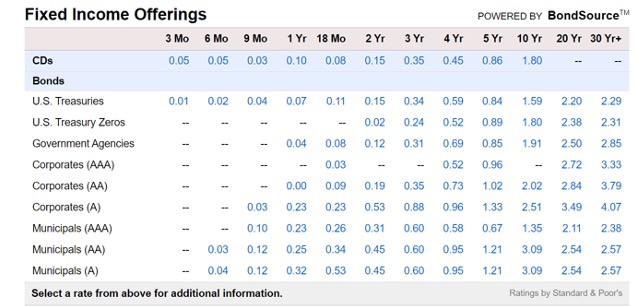

When Jo and I went through our retirement planning process, the experts recommended estimating 2% for inflation, 6% guaranteed for investment income (You can always get 6% in a CD or quality bond), 4% withdrawal, and you can depend on social security because it will rise with inflation. Well, the experts turned out to be all wrong.

While Sam and Sally’s investment portfolio may have earned double-digits, it lacked the safety of quality bonds or CDs. Today CDs and investment-grade bonds are guaranteed to lose buying power when inflation is factored in.

To earn potential double-digit returns, should they continue to have the bulk of their life savings at risk? Can anyone guarantee the market will grow on the same track for the next year; much less the next 25?

Investopedia said borrowing favors the debtor, with this caveat:

“This is because the borrower still owes the same amount of money, but now they have more money in their paycheck to pay off the debt.”

Sam & Sally no longer have a paycheck where inflationary increases help offset their cost of living. While their portfolio may have done very well, much of the increase was due to inflated stock prices, not dividends. They will likely have to sell assets to supplement their social security income to pay their bills.

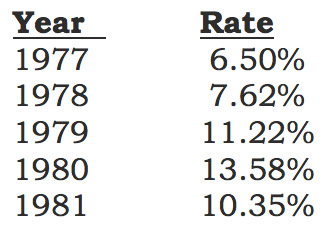

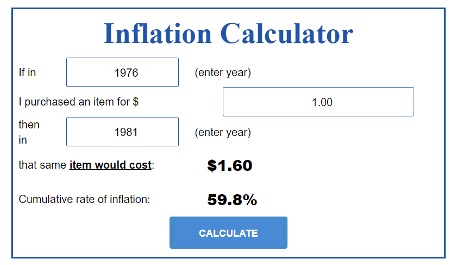

My experience is that it is exceedingly difficult to estimate expenses for anything beyond the short term. If Sam & Sally currently estimate spending $75,000 to maintain their lifestyle, what happens if they experience a period of high inflation like the Carter years?

Inflationdata.com supplies the inflation information for us:

The Inflation Calculator shows us the accumulated inflation was 59.8%.

If their $75,000 annual expenses rose at that rate of inflation, their current lifestyle would cost $120,000 annually, their $1,000 month cushion would be used up very quickly.

Yahoo Finance shows us during those years the market dropped for a five-year period before it recovered:

With their cost of living rising quickly, Sam & Sally would have to sell more stocks, (possibly at the wrong time) and withdraw more than 4% in order to pay their bills. While the market eventually recovered, they would no longer own many of their holdings.

I asked friend Chuck Butler for his thoughts:

“Just because the Gov’t’s CPI says that inflation is 4%, your inflation rate could be smaller, or larger than the stated CPI….

Let me start with something I know all about, health issues and costs. The cost of medical care is rising at a faster pace than inflation. An Emergency Room visit, and hospital stay could end up costing thousands of dollars.

Retirees may think their medical bills will be covered by Medicare, but that is not 100% accurate. The government is constantly raising Medicare insurance premiums.

Dennis, you have pointed out the fallacy in the “inflation rider” in social security benefits. Those benefits, and in some cases more, are quickly taken back in Medicare premium increases. Their Social Security “paycheck” will not keep up with real inflation.

While their stocks have performed well over the last decade, what happens when the market tanks? It could take years for the market to recover. When the tech bubble burst in the late 1990s, it took over 20 years to recover when adjusted for inflation. Retirees do not have the benefit of time like young people.

In addition, we could, as a country, experience another housing bubble bursting…. They could end up underwater, particularly with a vacation home, owing more than the current market price for the house.

These are not “out of the ordinary” things that could go wrong. They are very commonplace.”

When I weighed the “potential benefits” of borrowing to hedge against inflation, versus the “potential catastrophe” of being wrong, I realized that the decision is both logical and emotional. Remember the old saying, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.

I’m with Chuck, “Well, just because I say this, doesn’t mean it’s right for everyone, but for the most part it should be right.”

I define a comfortable retirement as living an acceptable lifestyle, without constantly having to worry about money. Personally, worrying about making monthly payments, or being forced to sell something at the worst possible time is not a risk I want to take. There are less stressful ways to hedge against possible inflation.

Get out of debt, and you will breathe easier….